Patricia Piccinini: Those Who Dream By Night

Haunch of Venison, 28 November 2012 – 19 January 2013

Tentatively entering Haunch of Venison to see the surreal, fantastical, and often disturbing works of hyperrealist Australian sculptor Patricia Piccinini, you are immediately greeted not by a sight, but by a sound: a glottal, gurgling, gulping that seems to choke its way around the corners of the gallery and into the foyer. It is From Within (2012), a video piece in which a woman sits passively in a cave, opens her mouth, and calmly allows a thick stream of unctuous ooze to pour endlessly from her body, letting the honey-like substance pool around her bluing ankles.

This initial meeting sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition in a number of ways, raising as it does a number of key themes: the grotesque, transgressive body; its reappraisal in terms of function and fecundity rather than fetishised aesthetic form; and the blurred lines between reality and the imaginary, particularly in the wake of scientific advancements. Most importantly, however, the video’s sickly, burbling soundtrack and images of regurgitation create a visceral sense of nausea which is steadily amplified by the remainder of the work on show.

Piccinini’s work preys on our insecure obsession with bodies, confronting us with hyperrealistic lumps of pure abhorrence: deformed sacks of self-contained, whiskery, veined skin, without faces or features; made, not born. They incite both revulsion and curiosity: Ghost (2012), which resembles a plucked raw turkey with a mane of flowing hair, has a particularly ominous medical scar, an angry red slit that one is compelled to penetrate with the same inquisitive, embodied probing as the doubting eponym of Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601-2).

Stripped of all social constructs, devoid of any medium for emotional or thoughtful expression – eyes, mouths, ears, gesticulating limbs – such amorphous parts re-present the body instead in purely biological terms, like plants. It is a comparison playfully evoked in a series of Hair Panels (all 2012), which presents us with blossoming branches of puckered, hairy anuses, reminding us that the flowers we so gladly imbue with aesthetic, social, and decorative meaning are actually just excretory organs like our own.

These emphases on the baser qualities of penetration, excretion, and reproduction loom throughout. Nectar (2012) secretes the same runny substance seen in From Within, pulsed out of yet another moist anal orifice, while in Sphinx (2012), a gaping, ichorous cavern hides the puce bulb of an engorged glans. Seeping and punctuated with errant hairs, misshapen moles, and scabby blemishes, these fleshy mounds force us to engage with precisely that which we repress; that is, our own, equally transgressive, bodies.

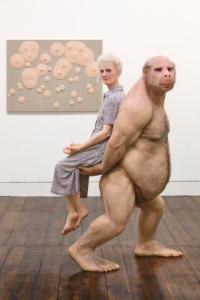

These abstract corporeal forms are certainly the most queasily provocative pieces in the show, but adding to their destabilising effect are some of Piccinini’s more overtly narrative sculptures. In The Coup (2012), a little boy with unnervingly long, hairy forearms and a distended upper lip is at once inhuman in his monkeyness and all the more human for it, his deformities embodying the playful, monkeying spirit of all small children. Upstairs, The Carrier (2012) fixes you with the dual gazes of an elderly woman and the apelike mutant who functions as her carriage, with the frail form of the former seeming considerably more fantastical and unreal than the latter.

Alternatively, The Lovers (2011) depicts two scooters curled around each other in a warm embrace, like deer. Ostensibly, it is simply the analogous reversal of the human-technology hybrids so central to Piccinini’s explorations; what is immediately striking, however, is how readily we engage and empathise with these anthropomorphised hunks of metal over their more frightening humanoid counterparts. Here, machines are more relatable than people, suggesting the higher significance we attribute to the ‘transcendental’ categories of shared stories and emotions over more base bodily concerns – which are in fact equally, if not more, universal.

Those Who Dream By Night, then, is an exhibition that forces us to rethink our relationships with bodies, with ‘normal’, and with ourselves. Piccinini’s sculptures uncover the tangible revulsion, fear, disgust and curiosity behind our anxious gazes, but also enable a sort of liberation: to stare, to touch, and to be. In this way, Piccinini’s works are an emetic to an audience that has gorged itself with Photoshop on the one hand and Embarrassing Bodies on the other. Most strikingly, however, the irrepressible physical sensations awoken and stoked throughout the show are an indisputable testament to the fact that sometimes, the body truly is more powerful than the mind – no matter what we might like to tell ourselves.